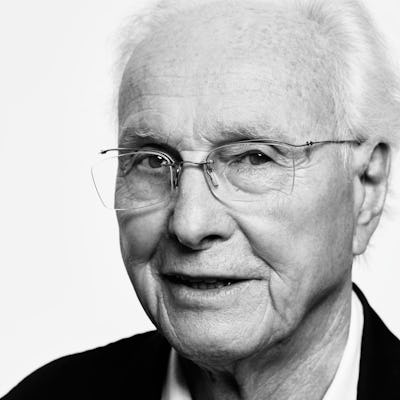

Since 1958, Luciano Bertoncini has been quietly and happily helping to create Italy’s design scene. Some say that Bertoncini, a man who eschews the spotlight, hasn’t received due credit for the influence he’s had on contemporary European modernism. But that doesn’t seem to bother him. “Bertoncini is neither envious nor bitter,” says Virginio Briatore in the introduction to Bertoncini’s 1999 retrospective. “He considers himself a lucky man, and he is always in good humor.”

Born in Feltre in 1939, Bertoncini studied technical drawing and, in 1957, began working with architect Vittorio Rossi in Treviso. With Rossi he learned integrity in architecture and got a chance to design not only buildings but also furniture. Rossi was a partner at Mobilindex – one of the few modern manufacturers in the area. “Those who were not around at the time will find it difficult to imagine the furniture that was made then,” says Bertoncini. “Louis XIV to rustic country!” His first piece, the futuristic and minimal, sprawling and transitional Zattera Bed, was well ahead of its time. It was included in the groundbreaking 1972 MoMA exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, which also featured his collaboration with Joe Colombo.

Bertoncini began working with Colombo after the master took a liking to Bertoncini’s Gronda Coat Hanger for Fiarm. The collaboration was cut short, however, with Colombo’s untimely death in 1971. Bertoncini was then tasked with completing Colombo’s Total Furnishing Unit for the 1972 show at MoMA. The New York Times called the exhibition “very large, costly and provocative,” and in the process helped solidify Bertoncini’s career.

In 1975, the designer was approached by Aprilia, the famous motorcycle manufacturer. This began a new phase for Bertoncini, as he shifted his attention from static objects to those built for speed. “To design a motorbike,” says the designer, “one has to enter the world of motorcycling, which is a very special habitat, almost maniacal: Every part of the bike has its rituals, its languages, its mechanisms.”

Capitalizing on his experience in mechanical engineering, Bertoncini creates perfectly balanced pieces that have no material or decorative excess. The people he’s worked with, however, credit his success to his personality as much as his genius. “In reality,” says Mino Bellato, “Bertoncini’s primary virtue is his sociable character: He gets on with everybody and has no fight with the world.”

Born in Feltre in 1939, Bertoncini studied technical drawing and, in 1957, began working with architect Vittorio Rossi in Treviso. With Rossi he learned integrity in architecture and got a chance to design not only buildings but also furniture. Rossi was a partner at Mobilindex – one of the few modern manufacturers in the area. “Those who were not around at the time will find it difficult to imagine the furniture that was made then,” says Bertoncini. “Louis XIV to rustic country!” His first piece, the futuristic and minimal, sprawling and transitional Zattera Bed, was well ahead of its time. It was included in the groundbreaking 1972 MoMA exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, which also featured his collaboration with Joe Colombo.

Bertoncini began working with Colombo after the master took a liking to Bertoncini’s Gronda Coat Hanger for Fiarm. The collaboration was cut short, however, with Colombo’s untimely death in 1971. Bertoncini was then tasked with completing Colombo’s Total Furnishing Unit for the 1972 show at MoMA. The New York Times called the exhibition “very large, costly and provocative,” and in the process helped solidify Bertoncini’s career.

In 1975, the designer was approached by Aprilia, the famous motorcycle manufacturer. This began a new phase for Bertoncini, as he shifted his attention from static objects to those built for speed. “To design a motorbike,” says the designer, “one has to enter the world of motorcycling, which is a very special habitat, almost maniacal: Every part of the bike has its rituals, its languages, its mechanisms.”

Capitalizing on his experience in mechanical engineering, Bertoncini creates perfectly balanced pieces that have no material or decorative excess. The people he’s worked with, however, credit his success to his personality as much as his genius. “In reality,” says Mino Bellato, “Bertoncini’s primary virtue is his sociable character: He gets on with everybody and has no fight with the world.”

1

Results

1

Results

View

Final Sale